This month’s newsletter is about Day of the Dead and how cooking connects me to my ancestors. Learn about Lima’s largest cemetery, an urban saint, and Andean mythology. Listen to a rock song about a sacred mountain, and read an excerpt from a poem about death and longing.

Dia de los Muertos

Día de los Muertos originated in Mexico, but cultures around the world celebrate Day of the Dead to honor their ancestors. Remembering the dead through stories, music, altars, and food keeps their spirits among the living.

In Lima, millions of people gather at Nueva Esperanza cemetery east of the city to celebrate Día de los Difuntos (Day of the Dead). The cemetery is one of the largest in Latin America, with over a million burial plots or mausoleums sprawling over hill sides and connected by dirt roads. Last year the cemetery closed because of COVID.

Communities in the Peruvian Andes also celebrate Día de los Difuntos, but honoring ancestors has been part of Quechua culture for thousands of years. The dead appear in Andean mythology’s three realms of the Inca: a snake represents the dead in the world below, the puma roams the surface world, and a condor flies in the world above.

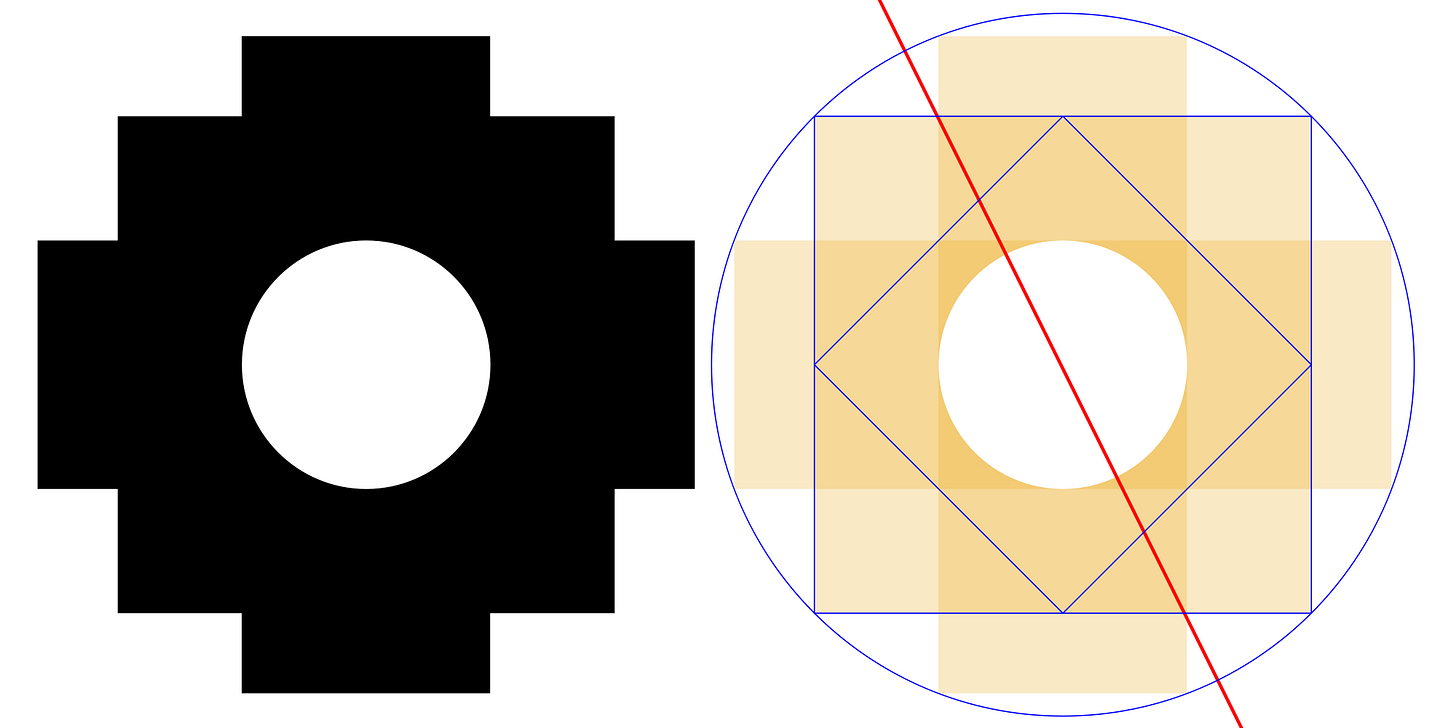

The Andean Cross

The realms of the Inca are symbolized in the Andean chakana cross. Its step pattern is a bridge that connects opposite worlds—light and darkness, day and night, and the human world to the higher world of the sun god Inti.

The Inca were astronomers, and marked the summer and winter solstice, so the geometry of the chakana represents the Southern Cross constellation. The chakana is often incorporated into ceramics, textiles, and sculptures.

Sacred coca leaves, held as a fanned-out trio, also represent the three realms. The leaves are present at births, engagements, weddings, religious festivals, funerals, and Día de los Difuntos altars—all milestones throughout life and death in Andean culture.

Sarita Colonia

In Lima, it’s everyday—not just Day of the Dead—that people visit the common grave where Sarita Colonia is buried. Though the church hasn’t canonized her, many Limeños consider her a saint and protector of the poor or migrants from the Andes who journey to Lima in search of a better life.

Sarita wanted to be a nun; however, at age 15 she had to take care of her siblings after her mother died. Despite an impoverished life, Sarita Colonia gave whatever she earned to the poor. At 26, she died of malaria.

Over time, Sarita gained devout followers who pray at her tomb and offer gratitude for her miracles. Throughout Lima, she is very much among the living and murals of Sarita are embedded in the urban landscape.

La Sarita

Peruvian rock band, La Sarita, honors Lima’s saint. Their song “Mamacha Simona” evokes melancholy and combines urban rock with Andean Huayno music, while the title refers to a sacred mountain near Cusco.

The Dead Woman’s Pass and Poem

One day in 2010, I ran the Inca Trail Marathon to Machu Picchu, a route that takes hikers four days to cover on foot across four high-elevation mountain passes. At almost 14,000 feet above sea level, Warmiwañusca, or Dead Woman’s Pass, resembles the silhouette of a woman lying down.

Pablo Neruda wrote about Machu Picchu after visiting the famed Inca ruin, and he also penned a poem called The Dead Woman. The powerful visuals and suffering impacted me ever since I first read it long ago:

if you, beloved, my love / if you have died / all the leaves will fall on my breast / it will rain on my soul night and day / the snow will burn my heart / I shall walk with frost and fire and death and snow / my feet will want to walk to where you are sleeping / but I shall stay alive

Dishes from the Dead

Pasta and Potatoes, the Peruvian Way is about the spaghetti with red sauce dish that I’ve inherited from my grandmother and that I learned to cook from my mother:

The combinado of tallarines rojos and papa a la huancaína is a unique mélange of Italian and Andean cuisines. It connects me not just to my childhood, but also to my mother’s youth, when my grandmother prepared this combinado for their family beach picnics during summer weekends in Lima of the 1940s.

Three Generations of Fathers, One Timeless Afro-Peruvian Breakfast tells the story of the rice and beans fritter that I learned to cook from my father, and that he learned to cook from his father:

As family cooks, we may not see our children or grandchildren grow up to make our traditional foods. All we can do is cook for them, and hope that the recipes are passed on. And if those dishes survive generations, then the cooks who prepared them will continue to live on among us.

This Día de los Difuntos, I’ve been thinking a lot about my ancestors, and how cooking connects me to them. Some dishes remind me of my grandparents who have passed, but other dishes, and their ingredients, connect me to my pre-colonial Indigenous ancestors. So when I cook, my kitchen becomes an altar, and my ancestors join me to cook our dishes.