This month’s newsletter takes a look back at the stories I wrote about the Sacred Valley village in 2022, and the people I interviewed that are shaping the food and drink culture there.

In 2019, I travelled to Peru with my wife. That was our last trip before the world shut down. Since then, we’ve started a family in our Pacific Northwest home, but through my stories I still travel to Peru, and the place that keeps pulling me is Ollantaytambo.

The Spirits of the Andes

2022 started with The Spirits of the Andes, my story for Whetstone about the distillers, brewers, and winemakers that have converged in Ollantaytambo to revitalize old spirits and create new categories.

At the foothills of the Inca ruins in Ollantaytambo, some 9,200 feet above sea level, sits Destilería Andina—a distillery that uses traditional methods and local ingredients to craft spirits that embody the terroir of the surrounding Sacred Valley and beyond.

At Destilería Andina, Haresh Bhojwani and his crew craft cañazo rum by double-distilling fresh-pressed sugarcane juice from the Amazon. With that base, they infuse the cañazo with Andean herbs and medicinal plants to create a compuesto that reminds me of green Chartreuse.

In collaboration with brewer Juan Mayorga of Cervecería del Valle Sagrado, they distill a white unaged whisky de jora from a mash of Andean corn that is germinated to make the ancestral chicha de jora beer.

“Instead of oak, it tastes like corn, like that smell of tamales, that moist, earthy, mother's kitchen beautiful comforting smell,” says Bhojwani about the unaged whisky de jora.

Fernando Gonzalez-Lattini of Apu Winery makes high-elevation wines in Curahuasi, but to make orujo from his production’s leftover pomace, he turned to Destilería Andina.

“Because we are distilling at altitude, things don’t burn in the still, alcohol is evaporating at a lower temperature,” Bhojwani says. “So, the orujo tastes very much like the wine, and where it comes from.”

Destilería Andina also distills a brandy, not from traditional grape wine but from a tuber wine that agricultural engineer and farmer Manuel Choque produces and calls oxalis, after the scientific name for oca.

“It’s like an aromatic pisco, generous, full-bodied, yet subtle, with the aroma of white flowers and herbs,” says Choque about the distillate.

After chatting with the distiller, brewer, winemaker, and farmer I realized that they are making Ollantaytambo into an epicenter of drink culture that could only exist in the Andes.

Pachamanca: Andean Earthen Oven

In The Underground Story of Slow Cooking for TASTE, I explore the ancestral technique that connects Indigenous cultures from the Americas to those in Australia, Hawaii, or New Zealand.

And in my contribution to Condé Nast Traveler’s A Guide to Barbecue Around the World, I wrote about Peru’s pachamanca:

For millennia, communities throughout Peru’s Andes Mountains have gathered around a pachamanca (the name of the earthen oven and the resulting dish) to bury ingredients in the ground and cook them with fire-heated stones.

In Ollantaytambo, pachamanquero Isaac Riquelme cooks in the pachamanca earthen oven at El Albergue, a 100 year-old hotel next to the train station. He told me that his parents and grandparents taught him to cook with huatias and pachamancas when he was a child.

“We season the ingredients with chincho that grows next to the oven—there’s also a bit of huacatay, garlic, and salt from Maras, and nothing else,” explains Riquelme about the marinade with Andean herbs that infuses the food with the distinctive aroma of a pachamanca—wild mint.

To Quechua people, pachamanca cooking is a sacred practice, so to express their gratitude before opening the pachamanca, they make offerings of food, chicha corn beer, and coca leaves to Apu mountain gods and Pachamama—Mother Earth, who provides the ingredients and now cooks them within.

Cooking in the earth is also a celebration, a feast of abundance honoring nature. And in the Andes Mountains, Quechua people play music, drink, and dance after uncovering the pachamanca.

Beyond nourishment, however, underground cooking is a common culinary language uniting global cultures, from the past to the present.

Humintas: Andean Fresh Corn Tamales

In This Tamales Story Is Still Being Written for TASTE, I connect culinary cultures across the Americas through corn tamales.

Everywhere there’s corn, there are tamales. From the Pacific Northwest to Patagonia, families make masa, wrap dollops of dough with savory fillings in corn husks, then steam them by the dozens. As small packages reminiscent of the comforts of home or of traveling street food, tamales are original Indigenous sustenance.

In the story, I write about tamales from Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, and North America—which has Indigenous fresh corn tamales that are similar to the humintas that Quechua people make in the Andes.

In Ollantaytambo, I interviewed Josefina Rimachi, chef at Chuncho, where she prepares humintas—fresh corn tamales—like her Quechua ancestors did thousands of years ago.

“From January to April, we harvest the fresh corn to make humintas. The rest of the year, we make tamales with dry corn,” says Rimachi about cooking seasonally.

But what struck me the most about our conversation was her inspiration.

Rimachi told me that when she was a young child, her father took her to a field in the Andes and asked her, “what do you see?” To which Rimachi replied, “nothing, there’s nothing here.” Her father then told her something that has stayed with her:

“Everything you need to cook is here, right here in front of you.”

And that is Rimachi’s approach to cooking—using local ingredients, that taste of earth, and cooking them using ancestral methods.

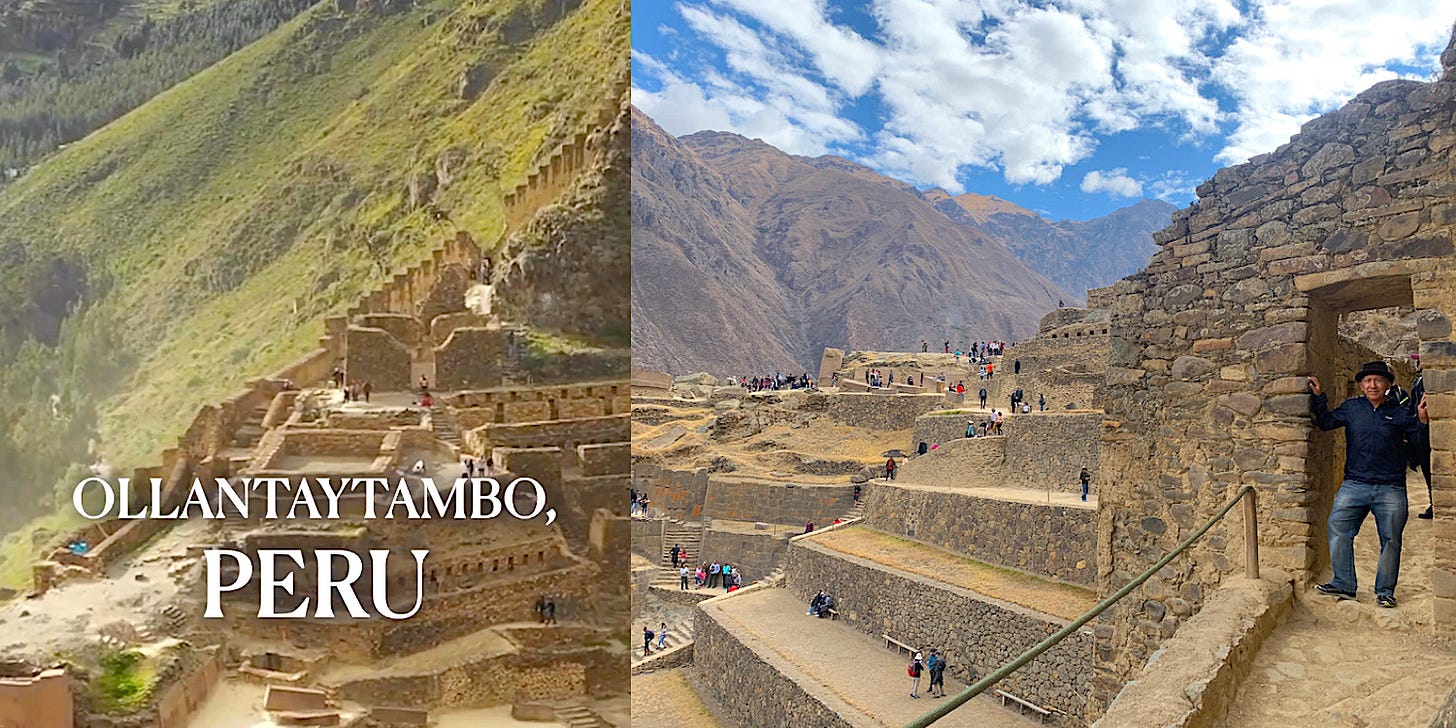

Traveling to Ollantaytambo

If you are inspired to visit Ollantaytambo, I invite you to read Condé Nast Traveler’s 23 Best Places to Go in 2023, where I write about Ollantaytambo and give recommendations for food, drinks, and lodging.

Ollantaytambo is best known for its archeological site, a hillside Incan fortress that draws travelers off the train to Machu Picchu. But of late, the village has also become a terroir-driven culinary epicenter in the Sacred Valley, with local entrepreneurs placing a new era of the Andean food and drink traditions on the world stage.

My wife and I are looking forward to the day we can take our children to Peru so that they can learn about their roots. And Ollantaytambo is at the top of our list.

Congratulations on getting your articles published in prestigious places, Nico.