Where can you go for your fix of pop-corn, corn-on-the-cob, grits, tamales, and corn beer? The Andes Mountains of Peru.

Mama Sara, The Goddess of Corn

Corn is an ancestral sacred crop in the Andes Mountains of Peru. There, Quechua communities cultivate corn, just like their ancestors did.

In the 1615 manuscript Nueva Crónica y Buen Gobierno, Peru’s Indigenous chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala illustrates farmers planting corn in September and harvesting in April and May. Seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are the opposite to North America’s.

The Quechua word for corn is “sara,” and Mama Sara is the Goddess of corn. Alongside potatoes, quinoa, tomatoes, hot peppers, coca, and wild herbs, corn is one of the most important sources of sustenance in the Andes. Today, about 55 varieties of corn grow in Peru.

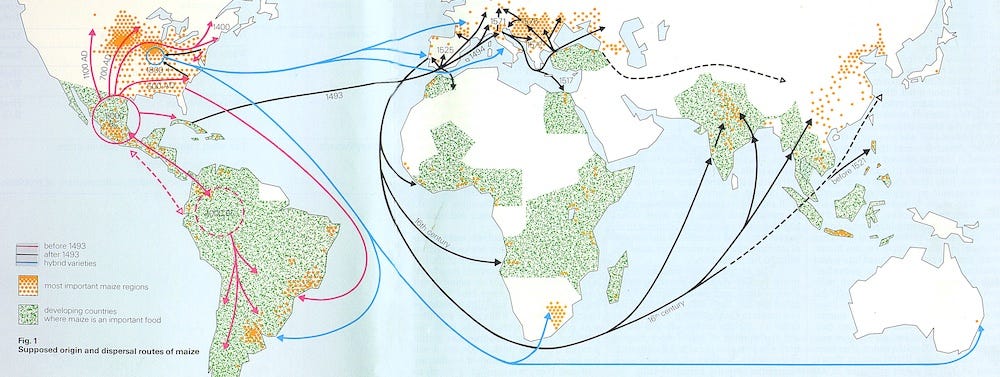

Corn also connects Indigenous cultures from Peru to those in Mesoamerica and North America, where communities thrive on maize.

Corn Foodways in the Americas and Beyond

Corn’s origin story is complex. Scientists believe that teosinte—an ancient Mesoamerican wild grass—is the ancestor of domesticated corn. However, DNA research suggests that:

Pre-colonial Indigenous foodways transported partially domesticated corn from Central America to South America, including the Andes.

In South America, Andean corn evolved separately and underwent domestication earlier than in Central America.

Once domesticated, corn from South America and the Andes returned to Central America to continue evolving.

So that would make the Andes a birthplace of maize. But regardless of location, corn is sacred nourishment to all Indigenous cultures.

Eventually, colonial foodways took maize to Europe, Africa, India, and Asia. But millennia before the industrialization of corn in the United States, Indigenous people cultivated corn for food and drink.

Indigenous Corn Foods

When was the last time you had pop-corn? According to a 2018 article on History, coastal communities in Peru made pop-corn from maize almost 7,000 years ago. They also ground corn into flour, or boiled it. And in the Andes, families cook corn in earthen ovens.

From the Andes to the coast, cancha—toasted corn kernels—is a popular snack, and street vendors hawk choclo con queso—corn on the cob with cheese. “Choclo” is Quechua for fresh corn, and “mote” means boiled corn.

The Inca also made sancu, a grits-like cornmeal, that they would carry on long journeys to mix with water for sustenance. This became the sango that colonists fed enslaved Afro-descendants.

But of all the corn foods, tamales is the dish that deeply connects cultures across the Americas. In my story for TASTE, I unwrap the past and present of tamales, from its Mexican heritage, to the Peruvian Andes, to Venezuela, to the Navajo Nation, and to the Deep South.

Everywhere there’s corn, there are tamales. From the Pacific Northwest to Patagonia, families make masa, wrap dollops of dough with savory fillings in corn husks, then steam them by the dozens.

Andean and Navajo communities make humintas and kneel down bread—fresh corn tamales. While in Venezuela, masarepa—boiled corn meal—is the base for arepas and hallacas, tamales that resemble empanadas.

In Mexico, however, communities nixtamalize dry corn to make masa for tamales. That’s the approach that Three Sisters Nixtamal in Portland, Oregon, is taking to prepare their fresh masa for tamales and tortillas.

But what are corn dishes without corn beer? Enter chicha de jora.

Andean Corn Beer

In my story for Whetstone, I sip the spirits of the Andes. Below is an excerpt about chicha de jora:

In the outskirts of Ollantaytambo, Cervecería del Valle Sagrado is brewing some of Peru’s first small-batch craft beer. But thousands of years ago, Andean communities were already germinating corn into jora to make the ancestral chicha de jora beer.

“It’s 8,000 years of fermentation behind that grain. So, it’s knowledge handed down mother to daughter for 8,000 years.”

To some, it’s an acquired taste, as the chicha de jora beer is actively fermenting when you drink it.

“It’s a really nice, unfiltered, wonderful light sour, with a lot of chewiness and body to it, like a big wheat beer, with a light frothiness to it.”

The aroma of open-air wild fermentation, in chomba earthenware vats, fills the dirt-floor rooms in the adobe homes that are chicherías. Ubiquitous throughout the Sacred Valley, these chicherías announce a freshly brewed batch by flying a red bag on a large stick outside their door.

“It used to be red flowers, so you could see how new that batch was by the freshness of those flowers.”

An Ode to Maize

In 1952, famed poet Pablo Neruda penned “Ode to Maize,” and a part near the beginning mentions the “heights,” or the Andes, of Peru:

Fue un grano de maíz tu geografía. / A grain of maize was your geography.

El grano / The grain

adelantó una lanza verde, / created a green lance,

la lanza verde se cubrió de oro / the green lance covered itself in gold

y engalanó la altura / and graced the heights

del Perú con su pámpano amarillo. / of Peru with its yellow tassels.

A Song About Maize

Huaynos are folk songs from the Andes Mountains of Peru that are full of melancholy and nostalgia. The lyrics of the Maíz huayno begins:

Maíz hermano / Maize my brother

Granito eterno / Eternal grain

Jinete de rayos negros / Horseman of black rays

Abrigo de niños tristes / Coat for sad children

Celebrating something so ordinary makes us realise the extraordinary in it - corn is delicious! Thank you for this cultural touchstone, Nico :)

Thanks for always teaching me something new! How incredible that there's going to be PNW Corn??!!! Also, Jocelyn Ramirez's book has not gotten the attention it deserves. It's fabulous!