Throughout Lima—from its streets, to tenements, to peñas criollas, to working class kitchens—where there’s food there is music.

Street Food, Music, and Dance

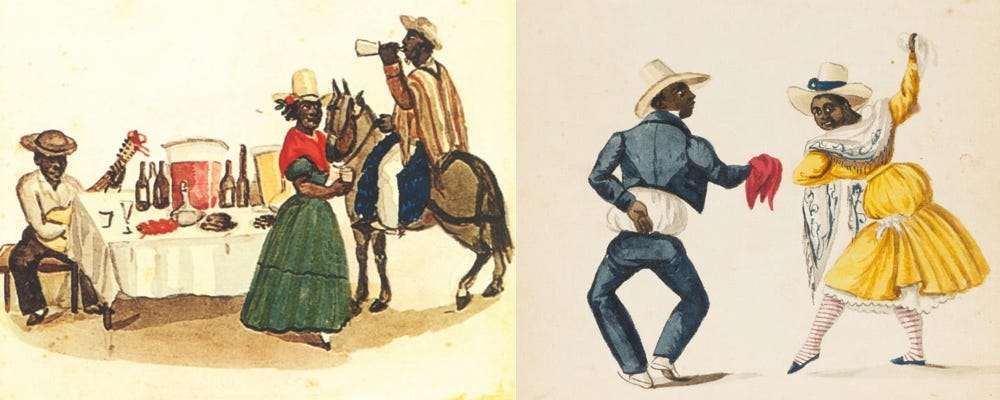

In the early 1800s, creole artist Pancho Fierro’s watercolors documented musicians alongside street food vendors and creole people dancing in the streets. Since then, Lima’s creole food and music have become inextricably intertwined because they share the same root: slavery.

Enslaved people gave Lima its Afro-Peruvian heritage that is the soul of its comida criolla (creole food) and musica criolla (creole music).

Two stories I’ve written explore this Afro-Peruvian heritage. The Origin of Lima’s Street Food describes Lima’s street food vendors and the dishes they hawked like tamales, empanadas, and causa.

The Soul Food of Black Peru visits El Carmen, an Afro-descendant community south of Lima, where a family of cooks and musicians preserve their culture through food, music, and dancing in the streets.

Quintas, Jaranas, Peñas, and Kitchens

In Lima, creole food and music came together in working class neighborhoods like Barrios Altos, where my parents grew up during the 1940s. There, families lived in quintas—crowded tenement buildings housing migrants of Andean, Chinese, Japanese, Italian, or Afro-descendant heritage.

The multicultural diversity of these families shaped the creole dishes they cooked.

But these quintas were also famous for hosting jaranas, all-night creole music jam sessions that brought together guitarists, singers, cajón percussionists, and dancers from the barrio. And it was creole food and drink that fueled these spirited jaranas.

Today, Limeños keep the jarana tradition alive at peñas, unmarked speakeasy venues with live creole music in the Bohemian Barranco neighborhood. Here is where late night revelers come to drink, dance, and eat creole food small bites that are piqueos.

But sometimes, a jarana is more intimate—instead of the streets or large quinta or peña, it takes place in a small kitchen or home.

When my parents hosted family reunions, my mom and I would prep and cook early. But first, we’d select some creole music from their collection of LPs. And when the stew was simmering we danced in the kitchen.

Playing music and dancing while cooking imbues creole dishes with another layer of criollismo and a profound soulfulness that you can taste.

That’s why I cook with music playing, and create playlists that are the soundtrack for dinner parties, cooking classes, and pop-up dinners. I want my food to transport you to Lima, and creole music facilitates the journey.

The Rhythms of Cooking

For almost as long as I’ve been cooking, I’ve played the Afro-Peruvian cajón—a hollow wood box drum that you sit on to play rhythms like the lively festejo, sultry lando, or the syncopated vals criollo that is Lima’s creole waltz. This vals evokes nostalgia and melancholy, so these days it’s mostly older Limeños like my parents that dance it.

Years ago, I cooked an Afro-Peruvian pop-up dinner, and to welcome the guests I stood at the head of a long communal table and sang an Afro-Peruvian song while percussing on the wood table top with my hands: zamba malato, lando 🎶, zamba malato, lando 🎶

I wanted the guests to listen and feel an Afro-Peruvian rhythm and song that was born out of slavery, just like the food they were about to eat.

Food and music share a deep rhythmic connection.

The ingredients that a cook brings together to make a dish are like the notes a musician plays for a song.

While recipes and sheet music suggest rhythms for hands to follow, in the end, hands perform innate choreographies that coax sounds and flavors.

Creole Food Playlist

In Peru's creole culture, music nourishes as much as food, and some creole songs are about specific dishes or creole food traditions. These are among my favorite food-centric songs:

“Viva el Perú y Sereno” describes the daily routine of street food vendors. From 6 a.m. until 8 p.m., they sold drinks plus sweet and savory foods.

“El Tamalito,” the diminutive term of endearment for a tamale, is an homage to the dish and its Afro-Peruvian roots.

“La Picantería” is about Leonor, a Black woman that cooks and sells picantes, small street food bites.

“Ollita Nomá” claims that sometimes a cooking pot (olla, or ollita in diminutive) is all you need, where nomá is really no más, or nothing else.

“A Saca Camote con el Pie,” means to unearth a sweet potato with your foot, but it really means to dance, to stomp your feet energetically. Similar, perhaps, to the English expression “to cut a rug.”

Wonderful article! Fantastic music. Wish I could be in Lima to enjoy all the amazing Peruvian culinary treats you described.

I enjoyed this post so much! Thank you for including links to all the musical selections and videos. Now I'd like to read it again, but while eating all the foods you describe! And hope that maybe one day I get a chance to dance and eat at a jarana myself.